henry david mallindine + jane mold

Henry was born on 15 January 1822 to William Mallindine and his wife Martha Edghill and he was baptised two years later at Christ Church in Spitalfields, on 19 April, along with his five year old sister, Martha Ann. At the time, Henry’s father was working as a Weaver and the family was living on Hope Street in Bethnal Green. Hope Street ran parallel to Minerva Street between the Old Bethnal Green Road and Nags Head Road, now Hackney Road, and although the street exists today, it was renamed Treadway Street in 1880 and all the houses were renumbered.

In 1840, Henry’s mother died and a year later, he was working as a General Servant and lodging with the Clements family in a house in Pundersons Gardens in Bethnal Green while his father and three youngest brothers were living on James Street.

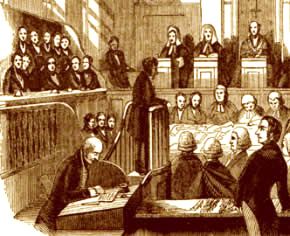

On 20 January 1842, Henry was convicted of theft at the Old Bailey for the first time. Mary Rose of Fleet Street in Bethnal Green testifed that shortly after hanging her laundry out to dry, she noticed that three shifts, a tablecloth and a sheet were missing from her yard. A shift was a light dress-like undergarment made of cotton or linen that was worn between the skin and clothing, and also worn as a nightdress, by most women at the time. She notified a nearby constable, George Trew, who found Henry walking down the street with the missing items in a bundle and arrested him a short time later. Henry testified that he was walking along Club Row when another boy offered him a penny to carry the bundle but the court did not accept his version of events and he was convicted of larceny. Henry was 20 years old when he was arrested but the court record lists his age as 15 years so it is possible he told the police he was younger to get a lighter sentence - and it may have worked as he was ‘recommended to mercy and confined for two months’.

On 10 July 1843, Henry was once again arrested and charged with stealing clothing from a residence in Bethnal Green Road. A policeman witnessed him take a waistcoat hanging outside and put it under his coat and then take a pair of trousers before running away. The policeman, James Attwood, caught him and took him back to the residence where John Hunter confirmed the clothes were his and that he had hung them and a number of other items outside the door earlier that morning. Henry denied the theft and stated that he was ‘running after two boys when he {the constable} took me, he did not find the trousers on me - he ran after me with them in his hand and the waistcoat he had afterwards - I do not know how he came by them.’ The constable confirmed his testimony and stated that Henry had dropped the trousers and the constable ‘took them up with one hand and took him with the other’.

Henry was convicted at the Old Bailey on 21 August 1843 and after police sergeant George Teakle appeared with a certifcate confirming his previous conviction, Henry was sentenced to transportation for seven years. He was held in Millbank Prison for four months and although his convict record lists his family members, it is not known if they were able to visit him before he was transported.

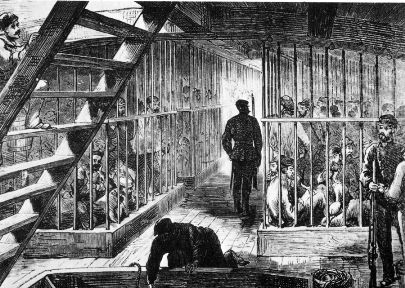

He was transferred to the SS Marion along with 300 other male convicts and sailed from London on 9 December 1843; the voyage lasted 126 days and the prisoners were kept confined for most of the journey. Conditions on board were poor and with so many people in a confined space and a poor diet, illnesses such as dysentery and scurvy were common and many convicts died at sea. On this voyage, four convicts died befoe the ship arrived in Hobart on 3 April 1844.

Between 1812 and 1853, over 74 000 convicts were transported from Britain to Van Diemen’s Land with the majority convicted of larceny and sentenced to seven years. The first convicts were transported to Botany Bay in New South Wales on board the First Fleet in 1788 and over the next 50 years, almost 80 000 more men and women were sent to the colony but when transportation to New South Wales was suspended in 1840, the focus shifted to the new penal colony of Port Arthur in the colony of Van Dieman’s Land. Shortly after all convict transportation ended in 1853, the colony was renamed Tasmania — after the first Europeran, Abel Tasman, to discover the island — in an attempt to distance itself from its convict past.

On arrival, each convict was interviewed and the reason for their conviction and a detailed physical description were recorded in their Conduct Report. Henry’s record notes that he was a Protestant and could neither read nor write. He was described as being 5’ tall with dark brown hair, grey eyes, a round face and a large nose and mouth. He also had a large scar on his right wrist and a number of tattoos including two anchors and the initials H and E on his right arm, a crucifix and anchor flag and the date 1843 on his left arm. The anchor was often used as a symbol of faith and hope and the initials may have represented Henry and a woman left behind in England.

On 22 September 1844, Henry was assigned to 15 months of labour at the Probation Station in the colonial town of Jericho some 70 kms north of Hobart. The area was first settled in 1816 and later became an important way station for coaches on the road from Hobart to Launceston. In 1840, the convict station was built to house the 200 convicts who were used to construct the new road and Henry was likely one of the men who worked on the road and surrounding infrastructure.

Shortly after arriving in Jericho, he was charged with insubordination as a result of openly refusing to obey an order and sentenced to hard labour. Three days later, he was charged again, with disorderly conduct, and sentenced to one month of hard labour in chains. Over the next four years, he faced ten additional charges including absenting himself from work without permission, gross misconduct for breaking his word, idleness, refusing to work, insolence and larceny under £5. The punishment for these charges ranged from time added to his probation, to solitary confinement, hard labour and in 1845, 36 lashes.

Despite his record of offences, Henry was granted a Ticket of Leave on 9 October 1849. The ticket was usually granted to those convicts who had shown through their good behaviour that they could be trusted with additional freedoms but as time went on, the tickets were granted to convicts once they had served a specified term of their original sentences. The required term for a seven year sentence was four years — or in Henry’s case four years plus the time added to his probation for his various offences. While in possession of a Ticket of Leave, a convict was required to find work within a specified area and earn his or her own keep; they were not allowed to change employers or leave the district without the permission of a local magistrate or the government but they were allowed to marry, own property or bring their families from Britain. Henry found work first in the Eastern Marshes, east of Jericho, and later at Sandy Bay near Hobart.

Once a convict’s original sentence had been served, they could apply for a Certificate of Freedom which confirmed that they had been restored ‘to all the rights and privileges of free subjects’ and were allowed to seek their own employment or leave the colony. A notice in the Launceston newspaper, the Cornwall Chronicle, confirms that Henry was granted his certificate on 1 March 1851.

Henry was living in Hobart and working as a Sail Maker when, on 2 May 1851, he had a son with Martha Martin but sadly, the baby boy died only three months later. When Henry registered the birth on 9 June, his son was still not named but by the time his death was registered on 12 August, they had named him Henry. No marriage record for Henry and Martha has been found but there is a convict record for a Martha Martin, aged 20 years, who arrived in Hobart on 3 December 1845 on a ten year sentence. She was originally from Cavan in Ireland and was working as a housemaid when she was convicted of stealing £11 from a person to buy spirits.

On 20 January 1852, Henry left Hobart alone and sailed on board the Flying Fish bound for Geelong in Victoria. The shipping index stated he was a gold seeker but if he did make it to the gold fields, he didn’t stay long as he left Port Philip on 12 March and arrived back in Hobart six days later. It seems he remained in Hobart for at least several years as a newspaper article in 1856 lists him as a signatory to a letter supporting R.W. Nutt as a representative for the new parliament.

But at some point, Henry left Hobart and sailed back to Victoria as he is listed in a Crown Grants Pay Office record in the town of Sale in eastern Victoria in 1872. Sale was a small town near Lake Wellington in East Gippsland but when gold was discovered further inland at Omeo, the town became an important coaching stop on the road between Port Albert on the coast and the gold fields. This resulted in a building boom between 1855 and 1865 with shops, hotels and offices filling the main street and by 1863, the town, with a population of 1800, became a borough with its own courthouse and newspaper, The Gippsland Times.

Henry again travelled back Tasmania where he married Jane Isabella Mold on 28 April 1877 at Chalmers Presbyterian Church in Hobart. Jane was 12 years older than Henry and this was most likely her second marriage as her parents were later listed as John Spence and Jane Elliott. It seems that Henry and Jane may have been living together in Sale and returned to Hobart to marry as a notice in the Hobart Times two weeks before their wedding reported that ‘Mr & Mrs Mallendine arrived from Melbourne on 11 April 1877’.

There is no record of how long they remained in Hobart, when they returned to Sale or any other records of their life in Sale until Henry’s death on 19 June 1896. His death certificate notes that 74 year old Henry lived on Hutchison Street and worked as a Labourer until his death from stomach cancer. He was buried at Sale Cemetery the following day but no headstone was ever laid at his grave. The death certificate was completed by the undertaker and contains several errors including the details on Henry’s marriage — married Jane Bell at Indigo, Victoria in 1859 — and his period of residence in Victoria which is listed as 46 years, or an arrival in 1851.

Jane remainded in Sale following Henry’s death and in 1903, she was living in York Street when she applied for and was granted an old age pension of 8 shillings per week. Jane died the following year, aged 96, and was buried next to her husband at the Sale Cemetery on 8 September.