isaac malandain + elizabeth frederick

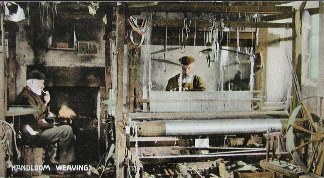

Isaac was born at the family home on Sclater Street on 22 June 1821 to Isaac Malandain and Jane Middleton but he was not baptised until just after his eighth birthday, on 15 July 1829 at St Matthew, Bethnal Green. His father was a Silk Weaver and on 25 May 1837, Isaac began his own seven year apprenticeship, indentured through the Draper’s Company, with James Fage, a Silk Weaver in nearby Wellington Row. The research completed to date indicates that Isaac’s father and James Fage were cousins.

Just months after he moved to the Fage house to start his apprenticeship, both of his parents died within weeks of each other and Isaac’s two younger sisters, Mary and Isabella, moved in with other family members. In 1841, Isaac was still living with James and Mary Fage and their six children in Wellington Row and working with James as an Apprentice Weaver.

On 5 May 1845, Isaac married Elizabeth Frederick, the first of his three wives, at St Philip in Bethnal Green and although his family may have attended, none were listed on the register as witnesses. He had served out his seven year apprenticeship the year before his marriage and was still working as a Weaver. Elizabeth was baptised at St Leonard in Shoreditch on 9 August 1824 and her parents, John and Elizabeth, were living in Mills Court at the time. When they married, Isaac was living at 28 Hart’s Lane and Elizabeth at 7 White Street. He was able to sign his name on the register but Elizabeth could only make her mark.

Less than a year later, they welcomed their first child when son Charles Frederick was born on 24 March 1846 at 166 Church Street in Bethnal Green. Isaac was still working as a Weaver but with wages dropping and competition from imported cloth, it was increasingly difficult for weavers to earn a living wage. On Thursday, 19 August 1847, Isaac was forced to appear before the Board of Guardians to apply for parish relief and when examined, he told the board that he lived at 10 East London Place in Martha Street with his wife and 17 month old son and confirmed his apprenticeship but no details on his financial situation were entered in the record.

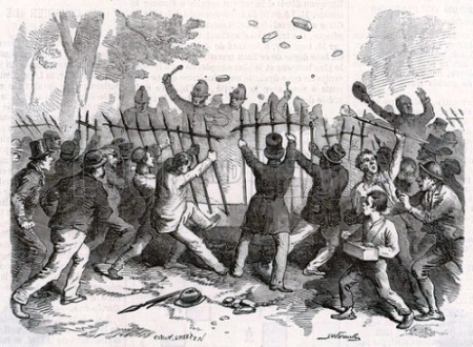

One year later, Isaac was one of a number of men arrested during a Chartist’s meeting in Bethnal Green. Chartism was a working class political movement that began in 1836 but was particularly active between 1838 and 1848. In 1832, the right to vote was granted to the middle class, specifically those who owned property, but the Chartists pushed for further reforms of the political system and demanded the right to vote for all men over the age of 21 as well as secret ballots, electoral districts of equal size and annual elections for Parliament. In 1848, the Chartists organized several demonstrations in an attempt to gain support for a petition they intended to deliver to Parliament but the government, fearing an uprising, responded with a show of force and drafted in the police, special constables and soldiers to disperse the demonstrators.

On 4 June 1848, the demonstrators gathered in Bonner’s Fields in Bethnal Green but they were dispersed by the police, including some on horseback, and after initially being driven into the surrounding streets, the police were once again ordered to clear the crowd. A special constable at the demonstration later reported on the events he witnessed:

At eleven o’clock Nova Scotia Gardens contained about 900 or 1000 persons of the lowest and most abandoned class, who had met to listen to a speech from a well-known inciter of the people. The first attempts to disperse this dangerous mob proved only partially successful; the mounted patrol arrived; a cowardly attack was instantly made upon them and the constables by a shower of stones; and after a severe conflict some of the aggressors were captured. On attempting to repulse a mob in a street in Gibraltar-walk, the scene became of a most alarming nature. Every tenement furnished a number of persons who threw missiles at the officers and yelled and hooted at them in terms of the most appalling execration...and loud complaints were made of the necessity for a complete social revolution by an equal distribution of the wealth of the country.

While clearing the streets surrounding Nova Scotia Gardens, the police came upon Isaac and believed that he was part of ‘the assembled mob’ and arrested him. On 20 June, Isaac appeared at the Worship Street Magistrate’s Court on charges of ‘assaulting police constable James Harrington in the execution of his duty’.

The Standard newspaper reported the details of Isaac’s trial:

The Constable stated that about twelve o’clock on the preceeding day he was engaged with other officers in dispersing a tumultuous mob which had assembled in Bird Cage Walk, Hackney Road, when the prisoner, who had taken a prominent part in the uproar, made a sudden stand at the corner of a street and pulled out a large clasp-knife, which he deliberately opened, and swore that he would stab the first man who ventured to approach him. Witness was about to seize him when the prisoner made a desperate thrust at him with the knife, the point of which pierced through his clothes and must have entered his chest but for the timely interference of another constable, who struck the prisoner a violent blow on the head with his truncheon and knocked him down.

The Times newspaper also published details on the trial and their reporter noted that Isaac was heard to call out ‘down with the ---police. Down with the --- specials’ when the constables tried to move him on. The dashes in the newspaper text are presumed to represent expletives that were not appropriate for publication. Their report also passed a rather harsh judgement on those charged and their involvement with the Chartist meeeting:

The prisoners all appeared to be in work and to have ample means of subsistence, and they had no excuse for mixing themselves up with such lawless proceedings. If there was to be a Government, and if men were to live as heretofore in peace and quietness, such acts as these must be repressed, and, but for the recommendation to mercy of the jury, he should certainly have inflicted the full punishment fixed by the law for the offence which they had been convicted.

Isaac was sentenced to 18 months’ hard labour with an additional requirement to enter into recognizanze to keep the peace for two years. When he was sentenced, his wife Elizabeth was five months pregnant and on 11 October, she gave birth to their daughter Elizabeth Jane at the Lying in Hospital in St Luke with the hospital matron, Mary Widgen, acting as the informant on the birth registration. Only 8 days after her daughter was born, Elizabeth died in the hospital and the cause of death was listed as ‘childbirth and peritonitis’. There is no record of what happened to Charles following his mother’s death but it appears that his baby sister was taken to the Bethnal Green Workhouse where she died on 23 March 1849 after suffering from mesenteric disease for 3 months. Terms like mesenteric disease or marasmus were often used to describe death in children due to malnutrion or any illness that resulting in physical wasting when the exact cause was not know. The informant on the death certificate was an official from the workhouse, AL Fairfield, and Elizabeth was buried under the name Jane at St Matthew, Bethnal Green on 28 March.

On 12 December 1848, Isaac petitioned the Right Honourable Sir George Grey, likely Sir George Grey 2nd Baronet who served as Home Secretary from 1846 to 1852, for an official pardon. He stated that the charge against him was unfounded and false and went on to detail his side of the story:

About 12 o’clock he went out in his shirt sleeves for the purpose of getting shaved and on arriving at a turning near the Bird Cage Public House he was met by two policemen with their truncheons in their hand who had been dispersing a body of person assembled opposite the said public house (of which meeting he was entirely ignorant at the time). He was about to cross the road to an Hair Dressers when he was knocked down by one of the constables while the other was beating him about his body. As he was falling a tobacco case and pocket knife fell from his waistcoat pocket and on perceiving them on the ground immediately picked them up for the purpose of replacing them again when they were seen by one of the policemen around him and asserted that he had taken the knife out with the intention to stab them. He was immediately taken off to a station house about a mile distant and during the whole distance received the most brutal treatment insomuch that it was deemed necessary that he should be taken to hospital. The police admitted he was alone and not with the rabble and that the knife was not open and therefore an attempt to stab either of them appears as inconsistent as it is untrue.

The petition ends with: ‘he was in possession of a good situation a happy home and an excellent wife. Blessings he had always highly prized but alas all that was dear to a man on earth are gone. His wife weigh’d down with grief only survived 4 months died leaving him two children under 3 years of age to the mercy of a cold and heartless world. He earnestly prays that your Lordship will take these circumstances into kind consideration and exercise your High Prerogative by rather letting a guilty person escape than suffer an innocent one to be punished.’

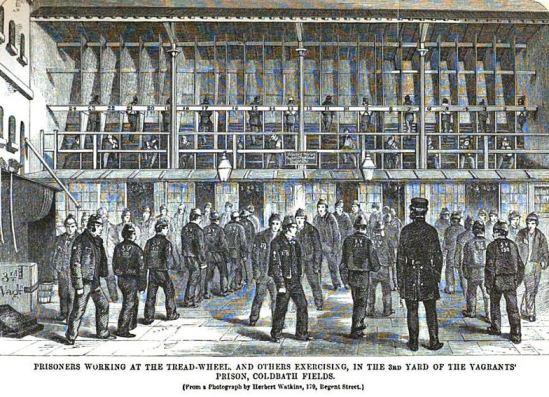

Although his petition was received by the Home Secretary on 18 December 1848, the pardon was not granted until 20 October 1849, two months before the end of his sentence. The pardon was signed by the Governor of the House of Correction of Coldbath Fields and by HM Command G Grey. It seems likely that Isaac’s request for a pardon would have to be approved by the governor of the institution in which he was imprisoned and since most prisoners on sentence for less than two years were sent to Coldbath, it would appear that this is where Isaac served his sentence.

Coldbath Fields Prison was located in Clerkenwell, on the site now occupied by the Royal Mail’s Mount Pleasant Sorting Offce, and housed men, women and children in separate blocks. Informally called the Steel, it was known for its strict regime of hard labour and its use of the treadmill which was a large wheel built with outside steps that prisoners were forced to climb like an everlasting staircase, walking for 15 minutes followed by 5 minutes rest, for 6 hours per day. Although it was used to grind grain, the main purpose was one of punishment with each prisoner separated by a wooden partition so they had no contact with the adjacent prisoner and saw only the wall in front of them.

There is no further record relating to Isaac or his son Charles until 27 September 1851 when the Board of Guardians of Mile End New Town submitted a removal order to the parish of Bethnal Green regarding five year old Charles. Sadly, the order noted that Charles had been abandoned by his father after being left with a family member: ‘that Martha Mallandine with whom the said Charles Mallandine was left on his father deserting him is a relative of the said Charles Mallandine.’ Martha’s identity is not yet known but an address, 15 Seabright Street, was written in the margin although it is not clear whether this relates to Martha. When he was returned to Bethnal Green, Charles was admitted to the workhouse and there is a fourteen year gap before he next appears in the public records — when he married Emma Elizabeth Tweed in 1865.

Martha Mallandine

Only one possible match for Martha has been identified so far and she is the daughter of William Mallindine and Martha Edghill - and Isaac’s second cousin. When the 1851 Census was taken on 30 March, Martha was living at 14 Granby Street and the head of her household was listed as Isaac Mallendine — aged 29, a Weaver born in Bethnal Green — and they were listed as husband and wife. In addition to Martha’s two children from a previous relationship, another son named Charles, born in Bethnal Green in 1846, appeared with the family. There is no record of Martha having a son named Charles and he does not appear with her family after this census. Martha and Isaac had a son named Isaac William and he was born on 18 October 1851, approximately one month after the above noted Martha handed Charles over to the parish guardians. Is it possible that Isaac began a relationship with his second cousin but deserted her months before their son was born?

Isaac left London and moved to Lancashire where he married Jane Cook in Prestbury on 25 April 1852. It is not known if he had any further contact with his son but when Charles married in 1865, he listed his father as Isaac Malandine, a Soldier, an occupation he took up when he enlisted in 1855 so it appears Charles had some knowledge of his father after he left London.