jaques mallandain + mary hawes

Jaques was the eldest son of Jaques Mallandain and Susanne Motteux. He was born on 2 November 1737 and baptised at Threadneedle Street the following day. Most of the records reflect the anglicized version of his name, James, and his children were baptised in the Church of England rather than the French Church.

James married Mary Hawes at St Mary, Whitechapel on 5 July 1759. The banns were called for three consecutive Sundays from 17 June to 1 July, and when they finally married, John Hawes and Mary Smith acted as witnesses. Mary was the daughter of John Hawes and his wife Elizabeth and was baptised at St Mary Whitechapel on 8 February 1729.

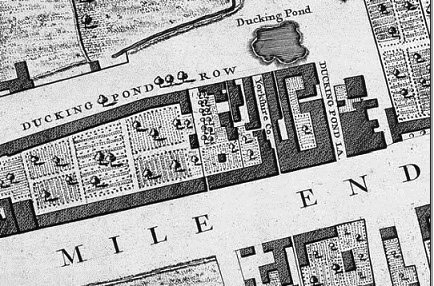

Soon after their marriage, James and Mary moved to Ducking Pond Lane in Whitechapel where they remained for the next four years. Ducking Pond Lane was named for the pond located at the corner of what is now Durward Street and Brady Street in Whitechapel.

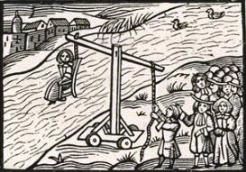

The Ducking Pond was a medieval punishment that involved being placed in a chair and repeatedly submerged in a river or pond. The punishment was most often handed out to shrews – defined as ‘a troublesome and angry woman who broke the public peace by habitually arguing and quarrelling with her neighbours.’ The Latin name for the offender, communis rixatrix, appears in the feminine gender and makes it clear that only women could commit this crime. ‘They place the woman in this chair and so plunge her into the water as often as the sentence directs, in order to cool her immoderate heat.’

Ducking Pond Row is famous as the site where Jack the Ripper’s first victim, Mary Ann Nichols, was found in August 1888. At that time, the street had been renamed Buck’s Row but the residents petitioned for a second name change due to the infamy surrounding the murder and in 1892, Buck’s Row was renamed Durward Street.

James and Mary had their first son one week after their first wedding anniversary. James was baptised on 15 July 1760 at St Mary, Whitechapel. In 1762, James’ step-father, Jean Des Claux, died and left him a £100 legacy that was to be paid out in instalments over a two year period. The legacy was a welcome bonus for this growing family as one year later, while still living in Whitechapel, they welcomed their second son, John, who was baptised at St Mary on 6 March 1763.

Whitechapel was originally part of the parish of Stepney but quickly developed as a suburb to the City of London due to its location on the main route from the city to Essex. The distinctly white-washed chapel that gave Whitechapel its name was built in the 13th century and became the parish church of St. Mary Matfelon about 1338. The original chapel was pulled down and rebuilt in 1673 but was destroyed by fire one hundred years later. The third St Mary’s was built and consecrated on 1 December 1882 but it too was destroyed when it was hit by a German incendiary bomb and gutted by fire on 29 December 1940. In 1966, the old church yard was cleared and turned in to a public garden.

One year after John was born, Mary Hawes received a legacy from the estate of Mary Towle. In 1737, Mary, a widow, had married Pierre Motteux, the elder half-brother of Susanna Rachel Motteux, Jaques’ mother. Mary Towle left a legacy of ‘£5 and two large silver spoons and some kitchen furniture’ to Mary and ‘four large silver spoons’ to Mary’s mother Elizabeth Hawes. There is no family relationship listed in the will so it is not know if there was a family tie between Mary Towle and Elizabeth Hawes or if they were simply friends.

James served as a Mariner for 15 years from 1765 until his discharge in August 1780. After his discharge, he applied for and was granted a pension from the Greenwich Hospital. Four years later, James applied to be an in-pensioner at the hospital and was admitted on 15 January 1784. The only record of his application is a Register of Admission that notes his medical status as ‘worn out.’ Although details of James’ service are not known, only those who served in the Royal Navy, Royal Marines or at the Royal Dockyards were eligible for a pension from the Greenwich Hospital. The Royal Naval Hospital for Seaman, later known as the Greenwich Hospital, was founded by Royal Charter in 1694 and it aimed to provide ‘the relief and support of Seamen serving on board the Ships and Vessells belonging to the Navy Royal…who by reason of Age, Wounds or other disabilities shall be uncapable for further service…and unable to maintain themselves. And for the Sustentation of Widows and the Maintenance and Education of the Children of Seamen happening to be slain or disabled.’

The hospital was designed by Christopher Wren and his assistant, Nicholas Hawksmoor, and comprised four separate buildings or courts. The hospital was built on the site of a derelict Tudor palace on the south bank of the Thames at Greenwich and the first building, King Charles Court, was completed in 1705 and the last, Queen Mary Court, was completed in 1742. The hospital was designed to house 1500 seamen known as in-pensioners. There were general wards for the more infirm but the majority of the hospital wards were partitioned into ‘cabins’ for single occupants or small groups.

The in-pensioners also received rations in the dining hall or a cash allowance in lieu so they could eat with and support their families. Although wives and families were allowed in as visitors, they never lived at the hospital and as a result the Greenwich area became a community of families living apart from pensioner husbands. In addition to the in-pensioners, the hospital also paid ‘out-pensions’ of £7 a year to retired or disabled seamen who lived in the community which allowed the hospital to support more seaman than could be accommodated as in-pensioners. Many of these out-pensioners continued to work in other professions as the pension paid was not sufficient to live on. In 1865, the last of the in-pensioners left the hospital and the building stood empty until the Royal Naval College moved from Portsmouth in 1873. Today, Wren’s great buildings are still in use by the Greenwich University and the National Maritime Museum among others.

No records, beyond the hospital admission, relating to James and Mary have been found although there is one possible related record. On 5 January 1786, James Mallandain, a widower, married Sarah Appleford, also a widow, at the church of St Sepulchre on Holborn Viaduct near Smithfield Market. The record could relate to this James who married a second time after Mary’s death but there is no further information available to confirm or exclude this record.